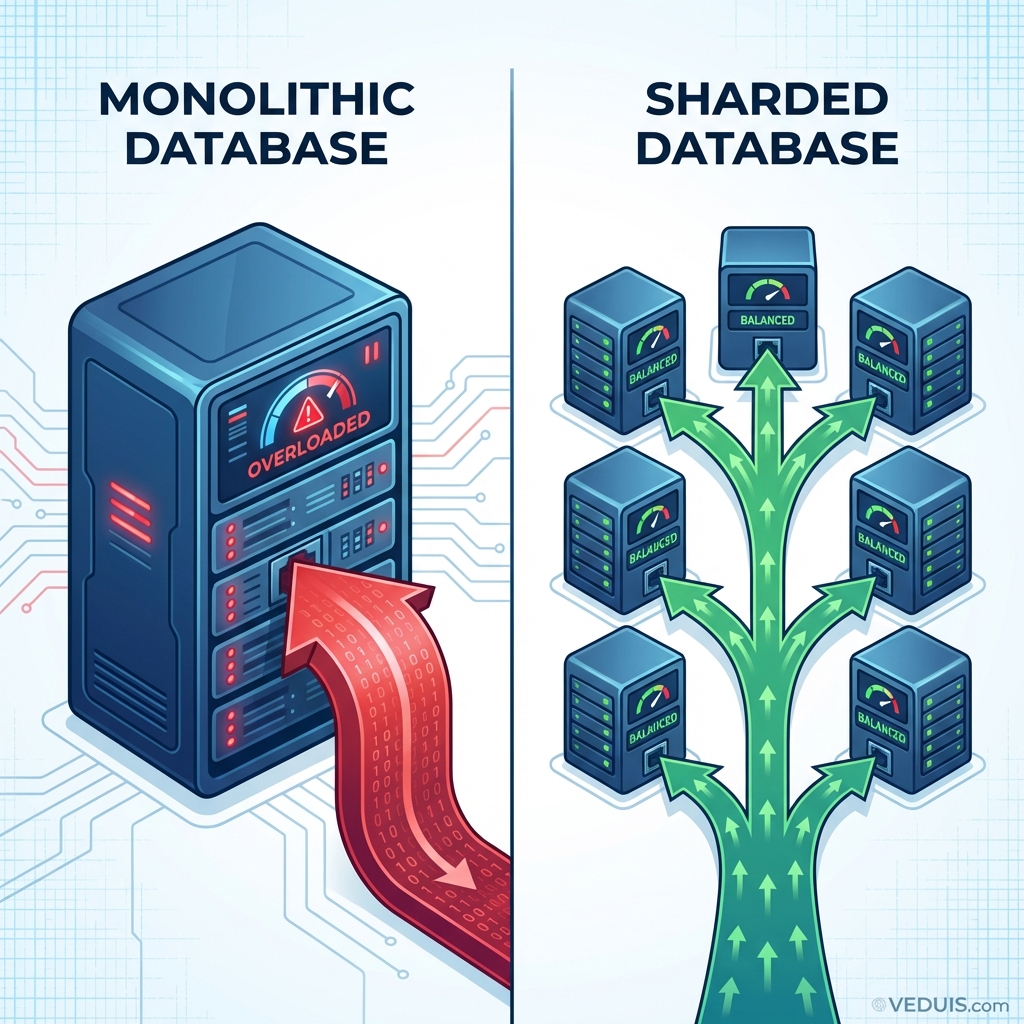

I’ve seen every growing SaaS reach a point where the database becomes the bottleneck. Queries slow down. Write latency spikes during peak hours. Backups take longer than acceptable maintenance windows. Vertical scaling hits hardware limits or budget constraints.

Database sharding provides a path forward by distributing data across multiple database instances. Each shard holds a portion of the total dataset, allowing reads and writes to parallelize across machines. Done correctly, sharding enables near-linear scaling. Done poorly, it creates operational nightmares and application complexity that haunts teams for years.

Understanding Sharding Fundamentals

Sharding horizontally partitions data across multiple database servers. Unlike replication, which copies all data to multiple servers, sharding divides data so each server holds a unique subset.

Key concepts:

- Shard - A single database instance holding a portion of the data

- Shard key - The column or attribute determining which shard stores each row

- Shard map - The lookup table or function mapping shard keys to shards

- Router - The component directing queries to appropriate shards

A customer database sharded by customer ID might place customers 1-10000 on shard A, 10001-20000 on shard B, and so on. Queries for a specific customer route to the correct shard based on the customer ID.

When to Shard (And When Not To)

Sharding introduces significant complexity. Before committing to this path, I always recommend exhausting simpler alternatives.

Try These First

Vertical scaling - Larger machines with more CPU, RAM, and faster storage often solve problems more simply than distributed architectures.

Query optimization - Slow queries might indicate missing indexes, inefficient joins, or unoptimized access patterns rather than fundamental capacity limits.

Read replicas - If read traffic dominates, replicas distribute load without partitioning data.

Connection pooling - PgBouncer or similar tools reduce connection overhead that often masquerades as database capacity issues.

Caching layers - Redis or Memcached offload repeated queries from the database entirely.

Signs Sharding Is Needed

In my experience, sharding becomes appropriate when:

- Single-server CPU or I/O remains saturated after optimization

- Write volume exceeds what one server can handle

- Dataset size exceeds practical single-server storage

- Regulatory requirements mandate data residency in specific regions

- Backup and recovery windows exceed acceptable limits

Most SaaS applications can scale considerably before requiring sharding. I’ve seen premature sharding create complexity without benefit.

Choosing a Sharding Strategy

The sharding strategy determines how data distributes and how the application accesses it. Here are the approaches I use.

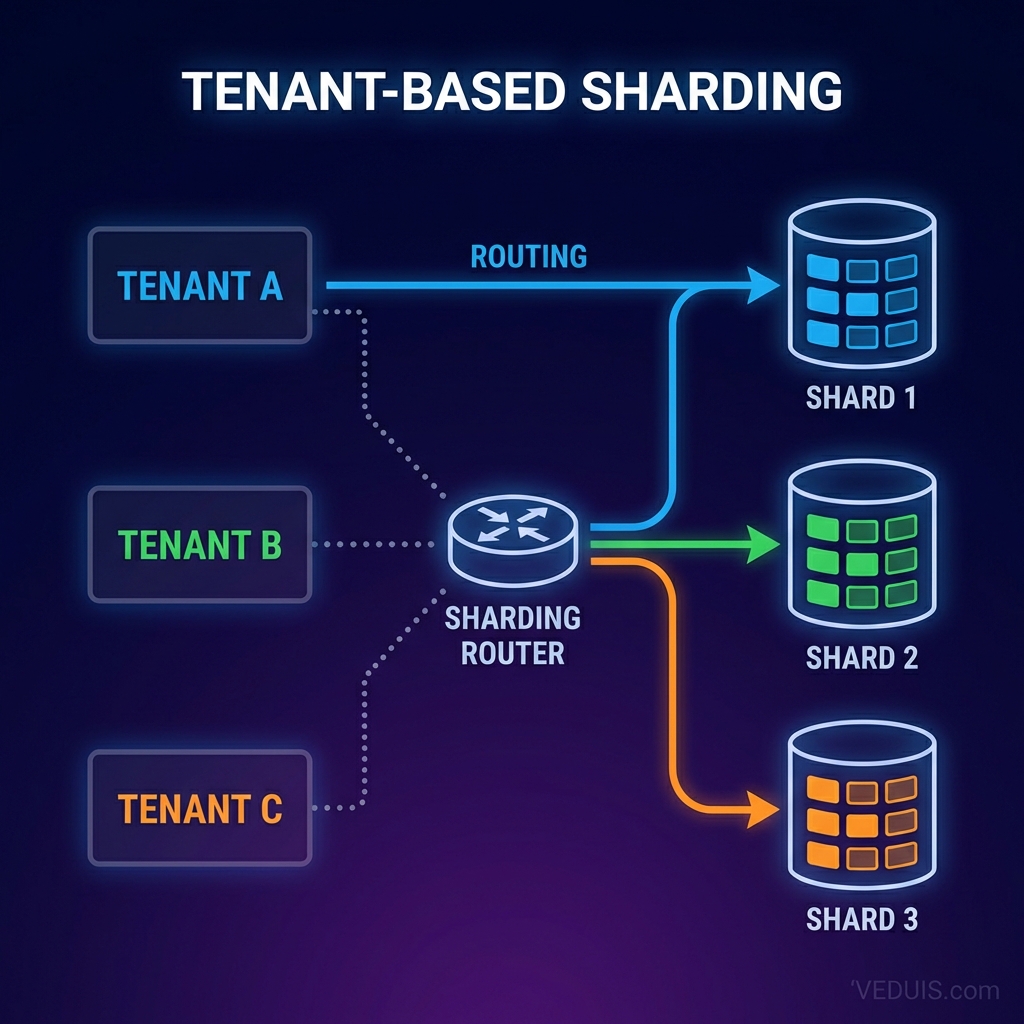

Tenant-Based Sharding

For multi-tenant SaaS, sharding by tenant ID offers compelling advantages:

Benefits:

- Natural isolation between tenants

- Queries typically scope to single tenants anyway

- Simplified compliance with tenant-specific data residency

- Tenant migrations between shards are conceptually clean

Implementation:

-- Each tenant's data lives entirely on one shard

-- Shard assignment based on tenant_id

-- Shard 1: tenants with id % 4 = 0

-- Shard 2: tenants with id % 4 = 1

-- Shard 3: tenants with id % 4 = 2

-- Shard 4: tenants with id % 4 = 3This approach works well when tenant data sizes remain relatively balanced. I’ve found that large tenants may require dedicated shards.

Range-Based Sharding

I divide data by ranges of the shard key:

Benefits:

- Predictable data location

- Range queries can target specific shards

- Easy to understand and debug

Drawbacks:

- Hot spots if recent data is accessed most frequently

- Rebalancing requires data movement

- Uneven distribution as ranges fill differently

I find range sharding works for time-series data where historical queries can target specific date ranges.

Hash-Based Sharding

I apply a hash function to the shard key for distribution:

Benefits:

- Even distribution regardless of key patterns

- No hot spots from sequential keys

- Simple routing logic

Drawbacks:

- Range queries must hit all shards

- Resharding requires rehashing all data

- No locality for related data

Hash sharding suits workloads with point queries rather than range scans.

Directory-Based Sharding

I maintain an explicit lookup table mapping keys to shards:

Benefits:

- Maximum flexibility in placement

- Easy to move individual entities between shards

- Supports complex placement logic

Drawbacks:

- Lookup table becomes critical infrastructure

- Additional query for shard resolution

- Lookup table needs its own scaling strategy

Directory sharding works well when placement logic is complex or frequently changing.

Application Architecture for Sharding

Sharding affects application design significantly. I plan these changes carefully.

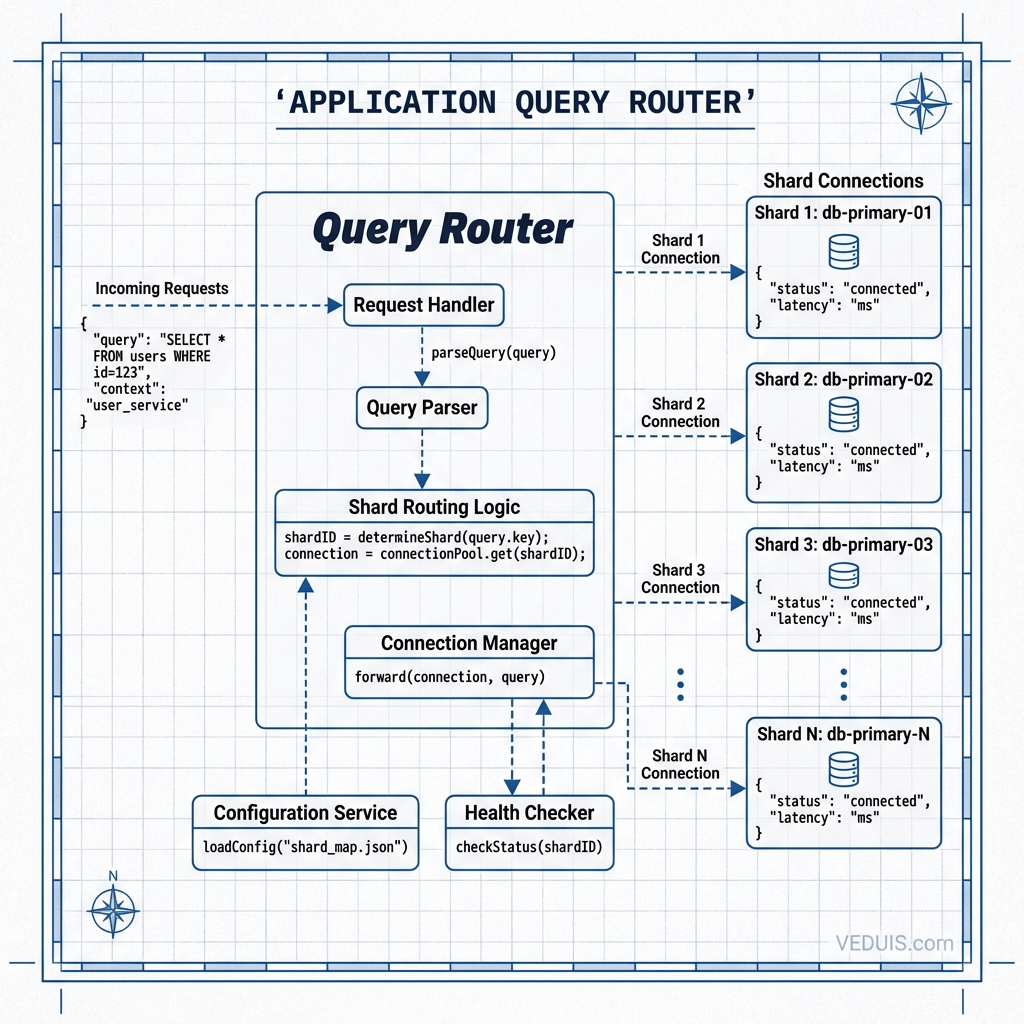

Query Routing

The application must route queries to correct shards. Common patterns include:

Application-level routing:

class ShardRouter:

def __init__(self, shard_count):

self.shard_count = shard_count

self.connections = self._init_connections()

def get_shard(self, tenant_id):

shard_index = tenant_id % self.shard_count

return self.connections[shard_index]

def execute(self, tenant_id, query, params):

shard = self.get_shard(tenant_id)

return shard.execute(query, params)Proxy-based routing: Tools like PgBouncer with custom routing or purpose-built proxies handle routing outside application code.

Database extension routing: Citus and similar extensions handle routing within PostgreSQL itself.

Cross-Shard Queries

Some queries legitimately need data from multiple shards:

Scatter-gather pattern:

def get_all_active_users():

results = []

for shard in all_shards:

partial = shard.execute(

"SELECT * FROM users WHERE status = 'active'"

)

results.extend(partial)

return resultsCross-shard queries are expensive. I design schemas and access patterns to minimize them.

Transactions Across Shards

Distributed transactions are complex and slow. Here are strategies I use to handle them:

Avoid when possible - Design data models so transactions stay within single shards.

Two-phase commit - Coordinate commits across shards, accepting latency and complexity costs.

Eventual consistency - Accept temporary inconsistency and reconcile asynchronously.

Saga pattern - Break distributed operations into compensatable local transactions.

I strongly recommend that most applications prefer single-shard transactions.

Schema Management

All shards must maintain consistent schemas:

# Apply migrations to all shards

for shard in shard1 shard2 shard3 shard4; do

psql -h $shard -f migrations/0042_add_column.sql

doneSchema migrations require careful coordination. I consider:

- Rolling migrations that work with both old and new schemas

- Feature flags to control code paths during migration

- Automated testing of migrations across shard topology

PostgreSQL-Specific Sharding Approaches

PostgreSQL offers several paths to sharding, from built-in features to extensions.

Native Table Partitioning

PostgreSQL supports declarative partitioning within a single server:

CREATE TABLE orders (

id BIGSERIAL,

tenant_id INTEGER NOT NULL,

created_at TIMESTAMP NOT NULL,

total DECIMAL(10,2)

) PARTITION BY HASH (tenant_id);

CREATE TABLE orders_p0 PARTITION OF orders

FOR VALUES WITH (MODULUS 4, REMAINDER 0);

CREATE TABLE orders_p1 PARTITION OF orders

FOR VALUES WITH (MODULUS 4, REMAINDER 1);

CREATE TABLE orders_p2 PARTITION OF orders

FOR VALUES WITH (MODULUS 4, REMAINDER 2);

CREATE TABLE orders_p3 PARTITION OF orders

FOR VALUES WITH (MODULUS 4, REMAINDER 3);Native partitioning provides query routing within one server. Partitions can be moved to separate servers using foreign data wrappers, though this adds complexity.

Citus Extension

Citus extends PostgreSQL with transparent sharding:

Capabilities:

- Distributed tables across multiple nodes

- Automatic query routing and parallelization

- Reference tables replicated to all nodes

- Distributed transactions support

-- Enable Citus and create distributed table

SELECT create_distributed_table('orders', 'tenant_id');

-- Queries route automatically

SELECT * FROM orders WHERE tenant_id = 42;

-- Routes to single shard

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM orders;

-- Parallelizes across all shardsCitus reduces application complexity by handling routing at the database level.

Foreign Data Wrappers

I also use postgres_fdw which allows querying remote PostgreSQL servers:

CREATE SERVER shard1 FOREIGN DATA WRAPPER postgres_fdw

OPTIONS (host 'shard1.db.internal', dbname 'app');

CREATE FOREIGN TABLE orders_shard1 (

id BIGINT,

tenant_id INTEGER,

total DECIMAL(10,2)

) SERVER shard1 OPTIONS (table_name 'orders');FDW provides flexibility but requires manual routing logic and has performance limitations for complex queries.

Migration Strategy

Moving from a single database to sharded architecture requires careful planning. Here’s the approach I follow.

Phase 1: Prepare Application

Before touching the database:

- Ensure all queries include shard key in WHERE clauses

- Eliminate cross-shard joins in application code

- Add shard-awareness to connection handling

- Implement feature flags for gradual rollout

Phase 2: Set Up Shard Infrastructure

Create target shard databases:

- Provision shard servers with identical schemas

- Configure networking and security

- Set up monitoring and alerting

- Test failover and backup procedures

Phase 3: Dual-Write Period

Write to both old and new locations:

def create_order(order_data):

# Write to legacy database

legacy_db.insert('orders', order_data)

# Write to appropriate shard

shard = router.get_shard(order_data['tenant_id'])

shard.insert('orders', order_data)Dual-write allows validation before switching reads.

Phase 4: Migrate Historical Data

Backfill existing data to shards:

def migrate_tenant(tenant_id):

shard = router.get_shard(tenant_id)

# Copy all tenant data

for table in ['orders', 'line_items', 'payments']:

data = legacy_db.query(

f"SELECT * FROM {table} WHERE tenant_id = %s",

[tenant_id]

)

shard.bulk_insert(table, data)

# Mark tenant as migrated

set_tenant_migrated(tenant_id)Migrate incrementally, validating each batch.

Phase 5: Switch Reads

Redirect read traffic to shards:

def get_orders(tenant_id):

if is_tenant_migrated(tenant_id):

shard = router.get_shard(tenant_id)

return shard.query("SELECT * FROM orders WHERE tenant_id = %s", [tenant_id])

else:

return legacy_db.query("SELECT * FROM orders WHERE tenant_id = %s", [tenant_id])Phase 6: Decommission Legacy

After validation period:

- Stop writes to legacy database

- Final data consistency verification

- Update all code to remove legacy paths

- Archive and decommission legacy database

Operational Considerations

I’ve found that sharded databases require evolved operational practices.

Monitoring

Track per-shard metrics:

- Query latency by shard

- Connection counts per shard

- Storage utilization per shard

- Replication lag if using replicas

I identify hot shards early before they become critical.

Backup and Recovery

Each shard needs independent backup:

# Parallel backup across shards

for shard in shard1 shard2 shard3 shard4; do

pg_dump -h $shard -Fc app_db > backup_${shard}_$(date +%Y%m%d).dump &

done

waitRecovery procedures must handle partial failures where some shards are affected while others remain healthy.

Rebalancing

Over time, shards may become unbalanced:

- Some tenants grow larger than others

- Hash distribution may not remain even

- New shards need initial data

I plan rebalancing procedures before they become urgent. Tenant-based sharding allows moving entire tenants between shards during low-traffic periods.

Common Pitfalls

Here are mistakes I’ve learned to avoid:

Sharding too early - Adding complexity before it is needed slows development without benefit.

Wrong shard key - A shard key that does not match access patterns creates constant cross-shard queries.

Ignoring hot spots - Popular tenants or time ranges can overwhelm individual shards.

Incomplete testing - Edge cases in routing and cross-shard operations surface in production.

Underestimating migration effort - Data migration is always harder than expected. Plan generous timelines.

In my experience, sharding represents a significant architectural commitment. The complexity it introduces persists for the lifetime of the system. I approach it deliberately, with clear understanding of both the benefits and the ongoing costs.